Original article

Cultural beliefs in the pharmacological management of parents of children with autism spectrum disorder

Creencias culturales en la gestión farmacológica de padres de niños con trastorno del espectro autista

Débora Rebeca Hernández-Flores1*  https://orcid.org/0009-0001-0080-2308

https://orcid.org/0009-0001-0080-2308

¹Master’s Degree in Management and University Teaching. B.Sc. in Chemistry and Pharmacy. Central University of Nicaragua, Faculty of Medical Sciences – Pharmacy, Managua, Nicaragua.

* Corresponding author. Email:  debora.hernandez@ucn.edu.ni

debora.hernandez@ucn.edu.ni

ABSTRACT

Introduction: decisions regarding adherence to psychopharmaceuticals in children with autism spectrum disorder are often the responsibility of parents, who may be influenced by cultural taboos that undermine therapeutic effectiveness.

Objective: to identify the cultural beliefs that influence the pharmacological management practices of parents of children with autism spectrum disorder at the special school “Divino Niño” in the city of Diriamba.

Methods: a qualitative methodology was used, employing a phenomenological and cross-sectional approach. Data collection was carried out through a focus group with six parents of children with autism and an in-depth interview with a psychiatry specialist. Data triangulation was conducted by organizing information into categories, subcategories, and emerging patterns in schematic format, along with theoretical triangulation. The ethical principles of scientific research were observed.

Results: the cultural beliefs of parents of children with autism shape their attitudes toward psychopharmaceuticals and adherence to treatment, leading them to prioritize alternative options and modify dosages. Consequently, pharmacological management is directly affected, influenced by the emotional impact of the diagnosis and resistance to medication due to fear of side effects.

Conclusions: there is a need for healthcare professionals to understand and work based on parents’ cultural beliefs in order to improve communication and treatment adherence in children with autism, without compromising evidence-based medical care.

Keywords: autism spectrum disorder; health belief model; parents; psychotropics.

RESUMEN

Introducción: las decisiones sobre la adherencia de psicofármacos en los niños con trastornos del espectro autista, es responsabilidad de los padres muchas veces condicionada por tabúes del entorno cultural que empañan la eficacia terapéutica.

Objetivo: identificar las creencias culturales que influyen en las prácticas de gestión farmacológica de los padres de niños con trastorno del espectro autista, en la escuela especial, “Divino Niño”, de la ciudad de Diriamba.

Métodos: se empleó una metodología cualitativa con un enfoque fenomenológico y transeccional. La recolección de datos se dio a través de un grupo focal con seis padres de niños con autismo y una entrevista en profundidad a una especialista en psiquiatría. La triangulación de los datos se realizó a través de la organización en categorías, subcategorías y patrones emergentes, en formato esquemático y la triangulación teórica. Se cumplieron los principios éticos de la investigación científica.

Resultados: las creencias culturales de los padres de niños con autismo moldean las actitudes hacia los psicofármacos y la adherencia al tratamiento, lo que conduce a priorizar alternativas y ajustes en la dosificación, de esa forma, influyen directamente en la gestión farmacológica, la cual se ve afectada por el impacto emocional del diagnóstico y la resistencia a la medicación, debido al temor a los efectos secundarios.

Conclusiones: existe la necesidad que los profesionales de la salud comprendan y trabajen en base a las creencias culturales de los padres para mejorar la comunicación y la adherencia al tratamiento en niños con autismo, sin comprometer la atención médica basada en la evidencia.

Palabras clave: modelo de creencias sobre la salud; padres; psicotrópicos; trastorno del espectro autista.

Received: 2025/07/07

Approved: 2025/10/20

From the current perspective of child health, autism spectrum disorder appears as a complex neurological condition that significantly impacts the development and quality of life of children and their families; this condition will accompany them throughout their lives, generating various needs for support and treatments.(1-3) Worldwide, the prevalence of autism—one in every 100 children—has shown an increasing trend, which has aroused multidisciplinary interest in the search for effective intervention strategies.(4-7)

International studies emphasize how cultural influences affect pharmacological treatment in children. A study in South Africa,(8) which explored the cultural perspective of autism in the Setswana community from the viewpoint of parents, concluded that ignorance and superstitious beliefs prevail, leading to late diagnoses. Similarly, in Mpumalanga, South Africa, within a school context, the lack of knowledge and the influence of cultural beliefs were identified as factors that hinder adequate treatment.(9)

In the Latin American context, according to the literature review by Alonso-Berdún,(10) the main determining variables in the pharmacological adherence of children with autism are social, economic, family, and individual factors. In addition, the importance of the relationship between these factors and adherence in adapting to the disorder was identified, including social support, life satisfaction, and family cohesion.

On the other hand, a study was conducted among countries such as Chile, Colombia, Argentina, and the Dominican Republic, with the participation of 21 parents, regarding stigmas related to autism. The findings indicated the importance of understanding the diagnosis at the beginning and during treatment, as well as communication difficulties with professionals upon receiving the diagnosis, and a lack of institutional support.(11)

Within this context, pharmacological management constitutes a therapeutic tool used to treat symptoms associated with autism.(8) However, the decision to resort to medication in the child population with this disorder is influenced by various factors, such as the cultural beliefs of parents, rooted in community traditions and values, which can shape the perception of the illness, attitudes toward medical treatments, and health care practices.

In Nicaragua, the most recent study conducted in the city of Managua reveals that parents experience pain, sadness, fear, and stress upon receiving their child’s diagnosis, and in some cases shame, which indicates cultural pressure surrounding conceptions of the disorder in Nicaraguan society.(12)

Particularly in the community of Diriamba, the present research aims to delve into the understanding of these cultural dynamics. As this institution is dedicated to the care of children with special educational needs, it becomes a relevant space to explore the experiences and perspectives of parents regarding the use of medication for their children with autism spectrum disorder. The objective of the study was to identify the cultural beliefs that influence the pharmacological management practices of parents of children with autism spectrum disorder at the special school “Divino Niño” in the city of Diriamba.

The study adopted a qualitative approach, structured under a phenomenological design with a descriptive scope. A cross-sectional design was used, with data collection limited to the first semester of 2025. This methodological approach facilitated a deep understanding of the experiences, perspectives, and social constructions of parents of children with autism regarding the use of medication within the context of the special school “Divino Niño” in Diriamba, a municipality belonging to the department of Carazo within the Metropolitan Region of Managua, Nicaragua.(13)

For this study, six parents of children with autism spectrum disorder who attended the special school “Divino Niño” in Diriamba and gave their consent to participate were included, as well as a psychiatry specialist, who, being the only one providing public care in the community, has daily contact with children and parents in her professional practice.

Data were obtained through a focus group with the parents and an in-depth interview with the specialist; in both cases, semi-structured question guides were used, and recorders were employed to obtain the literal information from the participants. The recordings were transcribed using the Turbo Scrib tool. Subsequently, a thematic analysis was conducted through data and source triangulation, based on the information obtained from the parents and the psychiatry specialist. Additionally, theoretical triangulation was carried out, considering the theory of resilience and spirituality as an adaptation technique to the diagnosis,(10,11) and the theory of mind,(14) which has been presented as the ability to attribute mental states (beliefs, desires, intentions) to others.

Permission for the study was obtained through the consent of the school’s administration and the two teachers of the autism classroom. The ethical principles established in the Declaration of Helsinki(15) and the bioethical principles of beneficence, non-maleficence, autonomy, and justice were followed.

As findings of the study, the cultural perceptions that shape the pharmacological management assumed by parents of children with autism in their role as caregivers were identified.

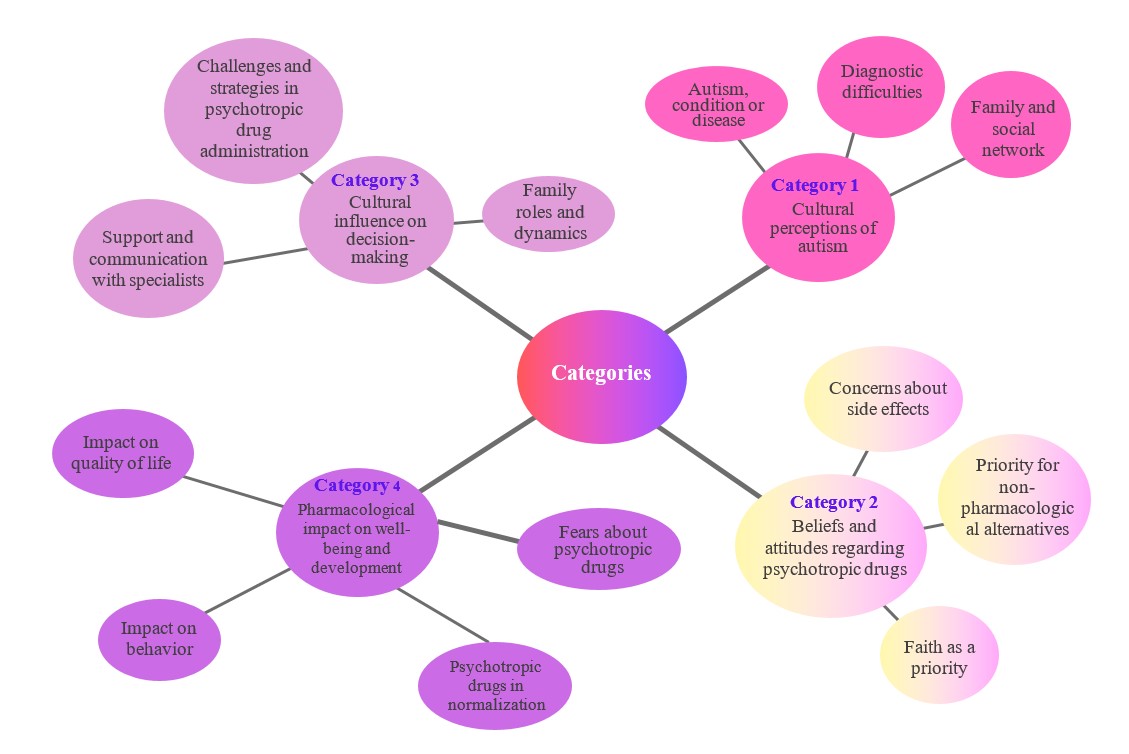

The thematic analysis produced four categories derived from the narratives of the parents and the psychiatry specialist, according to their clinical experience, in relation to the cultural beliefs that influence the pharmacological management of children with autism. Each of these categories, in turn, was classified into subcategories (Figure 1). In addition, an emerging theme was identified in the intervention with the parents in the study: the resilience they experience in their daily lives with their children diagnosed within the autism spectrum.

The phenomenon of pharmacological management of children with autism is intrinsically linked to an initial experience of shock and search, marked by the difficulty in naming the condition and the need to integrate faith and daily practices in medication management. The parents’ initial narratives describe a deep sense of confusion upon receiving the diagnosis. Autism is conceived in various ways, from an innate condition to a “disease” that evokes fear of functional loss. One parent recounted the intensity of this transition: “Autism is not a disease, it’s a state. It was destructive… I started to cry… I was afraid he would become a vegetable. I knelt before God — why did You allow this?”

Before specialized medical intervention, caregivers face a maze of recommendations, illustrating the initial difficulty in diagnosis: “Everyone sent us to a psychologist… a relative told us it wasn’t a psychologist but a neurologist.”

This search is permeated by faith and prayer, which are positioned as the first acts of health management within the community: “Well, God first, right? …a prayer, because God is always with us.”

Meanwhile, pharmacotherapy is seen as a health dilemma, based on the decision between what is moral and what is physical. Although the positive impact of psychopharmaceuticals on behavior and quality of life is acknowledged (“it helps with concentration, obedience, relaxation, attention”; “yes, it has helped him… he began to sleep, to be calmer”), there is constant fear of internal and long-term consequences. This fear is not only clinical but also cultural, associated with the potential harm to vital organs: “I feel it’s helping them… but I know that in the medium or long term it affects their health… stomach, liver, pancreas…”

This concern about side effects drives parents to actively seek non-pharmacological alternatives, prioritizing routines and affection to reduce the necessary dosage: “I wake him up every day at five in the morning so he can release energy and sleep without medication.”

Care thus becomes an art that combines behavioral routines, floral therapies, supplements (omega, magnesium), and, above all, the “necessary love.”

From a family perspective, medication management is configured as a dynamic and individual decision-making practice. Drug administration is not rigid, but rather adjusted daily according to the parents' perception of the child's condition. "I only give it strictly on specific days for the child... otherwise I don't give it to them" and "depending on the behavior we see in the children; we decide whether to give it to them or not." This intermittent management reflects the belief that the primary caregiver (typically the mother) holds total authority over the dosage: "I'm the one in charge" (a phrase repeated by multiple participants).

On the other hand, the specialist's perspective validates the existence of profound cultural barriers, but frames them as direct obstacles to therapeutic success and causes of treatment abandonment. The psychotropic drug as a "dumb" agent: the specialist confirms that cultural resistance manifests itself in the fear of sedation, perceived as a loss of cognitive ability: "They think psychotropic drugs will make them stupid because of the sedation they produce... so after two days they stop giving them the medication and don't return for the appointment."

"It reinforces that it is a community belief: "They resist using them because they think their children will become stupid."

It is reaffirmed that misinformation is a barrier, in the sense that there is interference from unvalidated sources, which undermines clinical confidence: "they always say that they read on the internet about the adverse reactions and that is why they did not continue giving the medication.". In clinical contrast (benefit versus belief) and in direct opposition to parental fear, the psychiatrist emphasizes the measurable benefit of the drug, not only in behavior ("it helps them learn more, to obey orders"), but in basic quality of life: "it improves the quality of sleep... it reduces hetero-aggressive actions, self-harm."

The comparative analysis of the narratives allows us to establish the essential structure of the phenomenon of cultural beliefs in pharmacological management, articulated in the four categories and subcategories shown in Figure 1.

Fig. 1 - Categories and subcategories of cultural beliefs in the pharmacological management of children with autism spectrum disorder at the "Divino Niño" special school, Diriamba.

Regarding the overarching theme, the most striking finding throughout the experience is: the resilience that parents develop in the daily management of the treatment. This resilience manifests itself in the creation of highly individualized administration strategies, such as "we experimented with different methods... we give it to them in their drinks, not all of them," or the forced patience required when using a syringe: "I inject one cc... until I get the full dose."

The essence of the phenomenon studied in the context of the special school “Divino Niño” in Diriamba lies in the constant tension between the clinical need for psychopharmaceuticals (for concentration, calmness, and sleep) and the cultural belief that perceives them as potential toxic agents. For parents, pharmacological management is a survival strategy rather than passive adherence. They do not reject treatment out of ignorance but negotiate it daily based on faith, intuition, and love, seeking a homeopathic balance. The phrase “Even if I don’t want to, we have to give it… otherwise, he convulses”

encapsulates this painful necessity to prioritize physical stability over adverse cultural beliefs.

From the perspective of pharmaceutical care, parents’ cultural beliefs (their role as dose managers, fear of long-term effects, and prioritization of alternatives) hinder the normalization of pharmacotherapy. The pharmacist must not only educate about the dosage but also about long-term safety and validate the care practices already employed by parents (routines, supplements). Communication must be sensitive to their perspective and recognize that non-adherence is, in reality, a culturally ingrained form of caregiving. Parental resilience becomes a therapeutic strength that should be leveraged by the healthcare team to ensure the child’s well-being.

The findings reflect an important connection between cultural perceptions, attitudes toward psychopharmaceuticals, and the perceived impact on children’s well-being and development. The perspective of the psychiatrist in Diriamba enriches this understanding, which has also been validated through observations from her clinical practice.

Parents see autism more as a “state” than as a “disease,” a key aspect influencing their initial approach. This perception is marked by the emotional impact of the diagnosis, generating a process of grief and search for meaning. This pattern emerges from the theory of resilience,(11) whereby parents develop positive thinking regarding the diagnosis as an effort to cope with an irreversible reality.(16)

The interviewed specialist points out that many parents tend to exhibit a “denial of the illness” and hope that their children will become “normal” (as they call it) over time, which complicates the acceptance of the medical diagnosis and, consequently, pharmacological interventions as part of long-term treatment. Quispe-Ramíez and Krystel(17) evidenced a negative, non-significant correlation regarding parents’ misconceptions about autism and the care practices they assume for their children, indicating that the more attentive parents were to their children’s care, the fewer erroneous beliefs they held.

The initial difficulty in diagnosis, as expressed by parents, highlights the need to improve referral systems and healthcare professional training. Parents’ experiences of being referred to other specialties reflect a gap in knowledge and coordination among different levels of care; this finding is directly related to the study by Kang-Yi et al.,(18) who found that initial diagnostic difficulties, discomfort, stigma, and discrimination are the predominant community attitudes toward autism and developmental disorders in the Korean-American community, demonstrating that both families’ and professionals’ understanding of autism and its care is affected by these community beliefs.

Similarly, Martinot et al.,(19) revealed that factors related to late diagnosis include socioeconomic status, symptom severity, level of parental concern, and family interactions with health and education systems prior to diagnosis. This finding relates to parents’ experiences when narrating the family and social support they received during the initial stages of diagnosis, which is often inadequate.

Likewise, this finding relates to the theory of mind, evidenced in the lack of professional or community knowledge about autism, which can lead to attribution errors. According to Pérez-Vigil et al.,(14) instead of attributing atypical behavior to a neurobiological difference, it is attributed to poor parenting, lack of willpower, or a spiritual and moral problem.

The research reveals a duality in parents’ beliefs and attitudes toward the use of psychopharmaceuticals. On one hand, they recognize their usefulness in controlling problematic behaviors such as anxiety and hyperactivity, which aligns with scientific evidence on symptomatic treatment of the disorder, according to Nunes-Costa and Carvalho-Abreu,(20) yet a significant concern about long-term side effects is a recurring theme. This fear is affirmed in the review by Persico et al.,(21) which concludes a great interindividual variability in clinical response and sensitivity to side effects in the population with the disorder.

This concern directly influences adherence and the prioritization of non-pharmacological alternatives. The adoption of routines, along with the use of supplements and floral therapies, demonstrates an active search for solutions that minimize dependence on psychopharmaceuticals. This suggests a culturally rooted approach in attachment and personalized care, which could influence decision-making regarding medication administration and lead to the suspension or modification of the dosage based on direct observation of the child’s behavior.

Simultaneously, religious faith becomes a fundamental pillar in addressing these concerns, as evidenced by expressions regarding acceptance and protective attachment toward the children, functioning as a protective strategy in the coping process. In this theory, religious interpretation is emphasized; it also suggests that autism is understood as something that goes beyond the medical and is situated within a spiritual dimension. This theory is supported by the study of Alonso-Berdún,(10) which confirms that one of the determining factors of parental resilience is spirituality.

The psychiatrist’s perspective provides valuable clinical insight into these findings, highlighting how these beliefs directly impact adherence and the challenges faced by a professional in their practice. Collaboration between healthcare professionals and religious or community leaders can be highly beneficial in incorporating faith as a positive resource to face difficult situations, without compromising evidence-based medical care. This aspect is especially relevant considering the depth of the finding on faith in the focus group and the psychiatrist’s knowledge of resistance to “mental illness” in the community, given that religious culture is deeply rooted in the population of Diriamba.

The specialist’s observations regarding the constant need to clarify the true purpose of medication (“behavior control and safety, not a cure”) and to dispel myths such as “becoming dumb” highlight the importance of education and dialogue. Woodman et al.,(22) established the importance of social support for parents of children with disabilities, showing in these cases a positive correlation between psychological well-being and social support.

Similarly, García et al.,(23) conclude in their study that parents of children with autism spectrum disorder face various needs, barriers, and challenges; they emphasize difficulties in accessing health services and the severe impact on family income, as well as stigma, discrimination, and feelings of helplessness. This reality aligns with the experiences of the parents in this study, in similar contexts.

Despite these challenges, parents have developed ingenious strategies to administer psychopharmaceuticals, revealing their commitment and creativity in facing medication-related challenges. However, they also highlight the need for greater support and guidance from healthcare professionals regarding administration techniques and the importance of adherence. The specialist reinforces these concerns about side effects and the search for alternatives, noting early treatment discontinuation due to sedation and parents’ consultation of the internet.

From a practical perspective, these findings have important implications for healthcare professionals. It is therefore essential that medical specialists and pharmacists understand parents’ cultural beliefs to facilitate effective communication and promote adherence.

These concerns present in parents align with the specialist’s experience when dealing with the expectation of “normalization” or “cure,” which arises from beliefs that go beyond the medical perspective. Another notable point was how parents tend to adjust the dosage or even discontinue medication based on their observations of their children’s behavior. The doctor noted that this represents one of the main barriers to effective treatment adherence, as parents often interrupt the medication after one or two days if sedation is observed, which can even lead to abandonment of psychiatric consultations. This finding relates to the research by Velarde and Cárdenas,(24) which raises new challenges regarding diagnosis and pharmacological efficacy in children with autism due to comorbidities and the emergence of major adverse effects.

However, the specialist attributes the use of psychopharmaceuticals to the development and overall well-being of children requiring this intervention, as evidenced by a decrease in hetero-aggressive episodes, greater concentration, improved sleep quality, among other benefits. This attribution is supported by the study of Ruggieri,(25) who notes that the purpose of pharmacotherapy is to improve undesirable behaviors, facilitate therapeutic intervention, optimize social integration, and achieve a better quality of life for the affected individual and their environment.

The culmination of this research raises questions that can be addressed in future studies, considered its main contribution: How can health and education programs effectively integrate cultural and religious beliefs in the treatment of autism spectrum disorder without compromising scientific validity, in order to reduce resistance to psychopharmaceutical medication? What strategies are most effective for empowering parents in the proper administration of psychopharmaceuticals and managing behavior in the presence of adverse effects?

The limitations of this study include the scarcity of national sources on the incidence of culture in adherence to pharmacological interventions for children within the autism spectrum. However, as a growing subline of research at the Central University of Nicaragua, these results can serve as a basis for new research questions on this topic. Additionally, this study could be applicable in other contexts, such as special schools in other departments, or specialized care centers for children within the autism spectrum in Nicaragua and other countries.

Parents of children with autism spectrum disorder express persistent fears regarding the long-term effects of psychopharmaceuticals, which influence their perception of their children’s well-being and development. Given that cultural beliefs about autism affect decisions regarding the pharmacological management of children with autism spectrum disorder at the special school “Divino Niño” in Diriamba, it is recommended to implement educational and support programs that address concerns about side effects, explore evidence-based non-pharmacological alternatives, and provide guidance on proper medication administration, without disregarding the cultural barriers identified by the psychiatrist.

1. Celis-Alcalá G, Ochoa-Madrigal MG. Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Rev. Fac. Med. (Méx.) [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 May 3];65(1):7-20. Available from: https://www.scielo.org.mx/pdf/facmed/v65n1/2448-4865-facmed-65-01-7.pdf

2. Ruggieri V. Autismo y burnout el agotamiento en las personas autistas, sus familias, docentes y terapeutas. MEDICINA (Buenos Aires) [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 May 3];85(Supl. 1):63-8. Available from: https://www.scielo.org.ar/pdf/medba/v85s1/1669-9106-medba-85-s1-63.pdf

3. Gaona VA. Etiology of autism. MEDICINA (Buenos Aires) [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 May 3];84(Supl. I):31-36. Available from: https://www.scielo.org.ar/pdf/medba/v84s1/1669-9106-medba-84-s1-31.pdf

4.World Health Organization, Newsroom. Autism. Key facts [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 May 3]; Fact sheets s/n [aprox. 4 p]. Available from: https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/autism-spectrum-disorders

5. Morocho-Fajardo KA, Sánchez-Álvarez DE, Patiño-Zambrano VP. Epidemiological profile of autism spectrum disorder in Latin America [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2025 May 3];1(2):1-25. Available from: https://saludycienciasmedicas.uleam.edu.ec/index.php/salud/article/view/25/23

6. UNICEF. Estrategias de enseñanza aprendizaje para la inclusión educativa de todos y todas con énfasis en trastorno del espectro autista [Internet]. República Dominicana; 2022 [cited 2025 May 3]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/dominicanrepublic/media/7991/file/Estrategias%20de%20Ensenanza%20Aprendizaje%20%7C%20Trastorno%20del%20Espectro%20Autista%20-%20PUBLICACION.pdf

7. Pan American Health Organization. Menthal health profile Nicaragua [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2025 May 3]. Available from: https://www.paho.org/sites/default/files/2020-09/MentalHealth-profile-2020%20Nicaragua_Country_Report_Final.pdf

8. Melamu NJ, Tsabedze WF, Erasmus P, Schlebusch L. “We call it Bokoa jwa tlhaloganyo”: Setswana parents’ perspective on autism spectrum disorder. Front Psychiatry [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 May 3];15:1381160. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychiatry/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1381160/full

9. Shilubane H, Mazibuko N. Understanding autism spectrum disorder and coping mechanism by parents: An explorative study. Int J Nurs Sci [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2025 May 3];7(4):413-8. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7644554/pdf/main.pdf

10. Alonso-Berdún A. Resiliencia in parents of children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: a multifactorial approach. EDUCA Revista Internacional para la calidad educativa [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 May 3];3(2):299-325. Available from: https://revistaeduca.org/educa/article/view/69/45

11. Santoso TB. Factors affecting resilience of mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder. International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2025 May 3];7(12). Available from: https://ijisrt.com/assets/upload/files/IJISRT22DEC334_(1).pdf

12. Jirón-Roque FC, Campos-Avellán JR. Actitudes y cambios en el estilo de vida de padres y tutores de niños/as con el trastorno espectro autismo en el distrito VII- Managua, Nicaragua durante el segundo semestre 2024 [Internet]. Managua: Universidad Central de Nicaragua; 2025 [cited 2025 May 3]. Available from: https://repositorio.ucn.edu.ni/id/eprint/33/1/Actitudes%20y%20cambios%20en%20el%20estilo%20de%20vida%20e%20padres%20de%20ni%C3%B1osas%20con%20EA.pdf

13. Hernández-Sampieri R, Fernández-Collado C, Baptista-Lucio P. Research Methodology. 6th ed. [Internet]. México: Mc Graw Hill Education; 2014 [cited 2025 May 3]. Available from: https://apiperiodico.jalisco.gob.mx/api/sites/periodicooficial.jalisco.gob.mx/files/metodologia_de_la_investigacion_-_roberto_hernandez_sampieri.pdf

14. Pérez-Vigil A, Ilzarbe D, Garcia-Delgar B, Morer A, Pomares M, Puig O, et al. Theory of mind in neurodevelopmental disorders: beyond autistic spectrum disorder. Neurol (Engl Ed) [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 May 3];39(2):117-26. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38272257/

15. Asociación Médica Mundial. WMA Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Participants. Ratified at the 75th General Assembly, Helsinki, Finland, October 2024 [Internet]. Helsinki: 18ª Asamblea Mundial; 1964 [cited 2025 May 10]. Available from: https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki/6

16. Miranda A, Mira Á, Baixauli I, Roselló B. Risk/resilience factors in families with children with autism. Association with evolution in adolescence. Medicina (B Aires) [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 May 3];83:53-7. Available from: https://www.scielo.org.ar/pdf/medba/v83s2/1669-9106-medba-83-s2-53.pdf

17. Quispe-Ramírez SK, Krystel S. Creencias erróneas y cumplimiento del cuidador en padres de niños con TEA en los cebe de lima centro [Internet]. Lima: Universidad Nacional “Federico Villareal”; 2022 [cited 2025 Jun 26]. Available from: https://repositorio.unfv.edu.pe/bitstream/handle/20.500.13084/6353/UNFV_FP_Quispe_Ramirez_Saskia_Krystel_Titulo_profesional_2022.pdf?sequence=1

18. Kang-Yi CD, Grinker RR, Beidas R, Agha A, Russell R, Shah SB, et al. Influence of community-level cultural beliefs about autism on families’ and professionals’ care for children. Transcult Psychiatry [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2025 May 3];55(5):623-47. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7008392/pdf/nihms-1068364.pdf

19. Martinot M, Giacobi C, De Stefano C, Rezzoug D, Baubet T, Klein A. Âge au diagnostic de trouble du spectre autistique en fonction de l’appartenance à une minorité ethnoculturelle ou du statut migratoire, une revue de la littérature systématisée. Encephale [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2025 May 3];35:223-30. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7547827/pdf/main.pdf

20. Nunes-Costa GO, de Carvalho-Abreu CR. The benefits of the use of psychopharmaceuticals in the Treatment of individuals with autistic spectrum disorder (asd): Bibliographic review. Rev RG de Estudos Acadêmicos [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2025 May 3];IV(8):240-51. Available from: https://www.revistajrg.com/index.php/jrg/article/view/232/337

21. Persico AM, Ricciardello A, Lamberti M, Turriziani L, Cucinotta F, Brogna C, et al. The pediatric psychopharmacology of autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review - Part I: The past and the present. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2025 May 3];110:110326. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33857522/

22. Woodman AC, Mawdsley HP, Hauser-Cram P. Parenting stress and child behavior problems within families of children with developmental disabilities: Transactional relations across 15 years. Res Dev Disabil [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2025 May 3];36C:264-76. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4425632/pdf/nihms635182.pdf

23. García R, Irarrázaval M, López I, Riesle S, Cabezas M, Moyano A, et al. Survey for caregivers of people with autism spectrum in chile: access to health and education services, satisfaction, quality of life and stigma. Andes Pediatr [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2025 May 3];93(3):351-60. Available from: https://www.scielo.cl/pdf/andesped/v93n3/en_2452-6053-andesped-andespediatr-v93i3-3994.pdf

24. Velarde M, Cárdenas A. Autism spectrum disorder and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: challenges in diagnosis and treatment. MEDICINA (Buenos Aires) [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2025 May 3];82(Supl. III):67-70. Available from: https://www.scielo.org.ar/pdf/medba/v82s3/1669-9106-medba-82-s3-67.pdf

25. Ruggieri V. Autism. Pharmacological treatment. MEDICINA (Buenos Aires) [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 May 3]:83:46-51. Available from: https://www.medicinabuenosaires.com/PMID/37714122.pdf

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author's contributions

Débora Rebeca Hernández-Flores: conceptualization, formal analysis, research, visualization, methodology and writing of the original draft.

Funding

Central University of Nicaragua.

Esta obra está bajo una licencia internacional Creative Commons Attribution4.0/International/Deed.

Esta obra está bajo una licencia internacional Creative Commons Attribution4.0/International/Deed.